Updated May 23, 2022

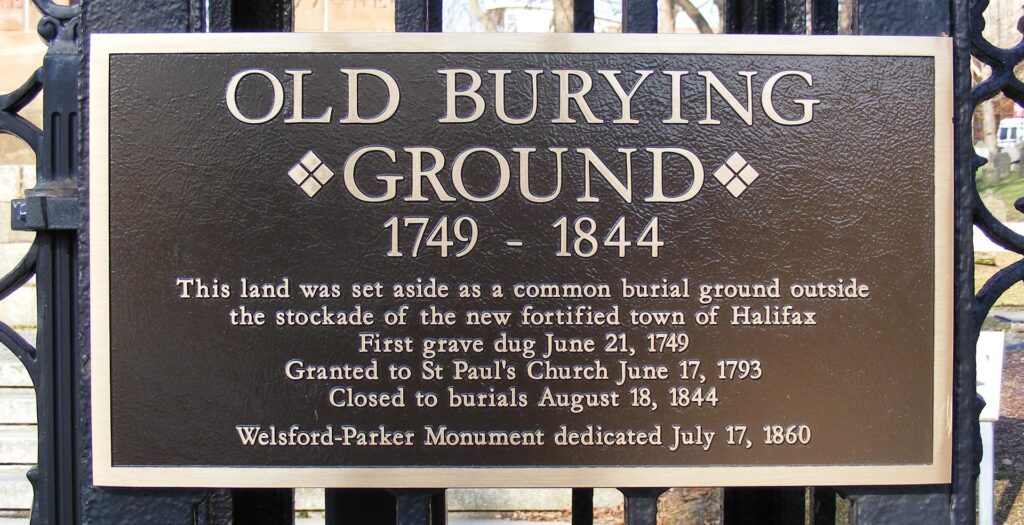

In the summer of 1749, as part of the new settlement of Halifax, an acre of land was laid out as a burying ground beyond the palisade protecting the town’s southern edge. A public cemetery receiving burials of persons of many faiths, its capacity was soon tested by a typhoid fever epidemic which killed over a thousand settlers in the winter of 1749-1750. Alarmed by the threat to public health, Governor Edward Cornwallis ordered that “all householders were … to notify deaths within twenty-four hours to one of the clergymen, under pain of fine and imprisonment.

Persons refusing to attend and carry a corpse to the grave when ordered by a justice of the peace were to be struck off the ration list and sent to prison.” [1]

In 1762 the size of the burying ground expanded from 1 acre to 2.25 acres. [2]

The title to the land was held by the Crown, but “the Church” – incorporated in 1759 as the Church of St. Paul – was responsible for recording burials conducted by its priests, and for maintaining consecrated ground.

Although the church needed the income, it could not charge fees for burial services because it did not own the Burying Ground. The Vestry of St. Paul’s struggled with this problem. At a meeting on March 31, 1777 they resolved:

“that every person of whatsoever denomination who shall order the church bell to be tolled for the funeral of any deceased relation or friend, shall pay towards the expenses of the repairs of the church five shillings, and also, that all strangers who shall chuse that their deceased relation or acquaintance shall be buried in the enclosed burying ground, shall pay towards the expenses of keeping the said ground, the sum of ten shillings.” [3]

Title to the Old Burying Ground was granted by the Crown to St. Paul’s in 1793, at last allowing burial fees to be charged.

Title or no title, Haligonians continued to view the Old Burying Ground as their nondenominational town cemetery.

In 1801 St. Matthew’s Church received a communication from the Rector, Churchwardens and Vestry of St. Paul’s:

“…and whereas doubts have been suggested whether the rights of the Protestant Dissenters from the Church of England to be buried in the said ground commonly called the Old Burying Ground on payment of the like fees as are now paid for the burial of any of the parishioners of the said Parish Church of Saint Paul … we, the said Rector, Church Wardens and Vestry for the time being of the said Parish Church of Saint Paul, for ourselves and our successors in office, do by these Presents testify, acknowledge and declare, that the Members of the Protestant Church or Congregation of Saint Matthew in Halifax aforesaid, as well as the Protestant Dissenters from the Established Church of England, have had since the first settlement of this Town of Halifax and Parish of Saint Paul, and still have and forever hereafter shall have good right and claim to bury their dead in the said ground commonly called the Old Burying Ground, on payment of the same dues and fees to the Rector, Sexton and other Officers for the time being of the said Parish Church of Saint Paul…” [4]

The Old Burying Ground was closed to burials in August 1844. In the 95 years of the cemetery’s use, it received burials of approximately 12,000 people, parishioners of St. Paul’s and St. Matthew’s, members of the British Army, the Royal Navy, seafarers, travellers, and citizens of Halifax of other denominations.

“As a result of ecclesiastical and community pressure periodically being brought to bear on St. Paul’s, the Old Burying Ground has been saved the fate of many of Canada’s urban burying grounds. In most cases these sites simply disappeared as they became swallowed up by expanding cities. Such was the fate of another 18th century burying ground, situated near St. Mary’s Basilica in Halifax.” [5]

The future of the Old Burying Ground was formally secured when it was declared a Municipal Heritage site in 1986, a Provincial Heritage Property in 1988, and a National Historic Site in 1991 – the first graveyard in Canada to receive such a designation.

The Relevance of the Old Burying Ground

The Old Burying Ground is a visible expression of all that Halifax witnessed in its first ninety-five years. The oldest existing stone dates from 1752, the grave of a child, Malachi Salter. A 1757 stone marks the grave of John Connor, Halifax’s first ferryman. In 1762 Father Pierre Maillard, Roman Catholic missionary to the Micmacs, was buried by his friend, the Reverend Thomas Wood, Vicar of St. Paul’s. Maillard’s body was later removed to St. Mary’s Cathedral churchyard across the road from the burying ground. The first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia, and Lieutenant Governor, Jonathan Belcher, was buried here in 1776. A flat tombstone, inscribed in part ” his fortune suffered shipwreck in the storm of civil war”, marks the 1784 grave of the Loyalist Edward Winslow.

Reflecting Halifax’s position as a military and naval base are the tombstones of Lieutenant Charles Thomas of the Royal Fusilier Regiment, and Lieutenant Benjamin James, the Royal Nova Scotia Regiment. Both young officers died in 1797, their graves marked by Lieutenant General His Royal Highness Prince Edward.

During the War of 1812 a stirring naval funeral brought to the Old Burying Ground the body of James Lawrence, Captain of the defeated U.S.S. Chesapeake. Weeks after his burial in June 1813, an American vessel flying a flag of truce sailed into Halifax Harbour, asking for Captain Lawrence’s body for re-burial in his own country. Permission was granted, and under cover of darkness the coffin was exhumed, eventually to be buried in Trinity Churchyard, New York. John Samwell and William Stevens, a midshipman and the boatswain of the victorious H.M.S. Shannon were buried close to the future site of the Sebastopol Monument.

Major General Robert Ross, to quote his tombstone, “was killed at the commencement of an action which resulted in the defeat and flight of the troops of the United States near Baltimore, on the 12th Sept. 1814”. His troops captured Washington, burning several public buildings including the President’s mansion. The pale limestone building was so badly stained by smoke that it had to be painted white. Ross is remembered by Americans for inadvertently giving them a name for the White House, and through his use of rockets in battle, inspiring their national anthem. Thousands of Halifax women could be represented by Sophia Connor, mother of eight, who died in the cholera outbreak of 1834.

Of great heritage value, the stones in the cemetery speak of epidemic and hurricane, love and tragedy, war, victory, and daily life in 18th Century Halifax. Here lie the bones of John Howe, the father of Joseph Howe, Samuel Cunard’s young wife Susan, and William Bowie, who lost his life in a duel with Richard John Uniacke, Jr., son of the Attorney General of Nova Scotia. The stones are often beautifully carved with motifs illustrating the funerary conventions of the time: angel’s heads, wings, cherubim, trumpets, urns, or weeping willows.

“One remarkable box tomb, which may have been carved by [James] Hay’s workshop, is the Bulkeley monument of 1796. Its two end panels depict Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and the Last Judgement Day. The Adam and Eve tableau are a common theme in Scottish grave art, but only two other examples are known to exist in North America. A second marker of exceptional quality is the Lawson children stone of 1784. This perfectly preserved slate marker was carved in the Boston area and depicts a pair of energetic trumpeting angels.” [6]

Reflecting the hundreds of Halifax children who did not live to grow old, the six Lawson children were remembered by their grieving parents with this epitaph:

What once had virtue, grace and wit

Lies mouldering now beneath our feet

Poor mansions for such lovely guests

Yet here they sweetly take their rest.

Cold is their bed and dark their rooms

Yet angels watch around their tombs

Pleased they patrol, nor sleep, nor faint

They only watch their fellow saints

Till the loud mansions of the skies

Relieve their guards and bids them rise.

“The Old Burying Ground in Halifax, Nova Scotia, is a mid-18th century burying ground, which received a second lease on life in the mid-19th century and is presently undergoing a careful restoration and rehabilitation. Set apart as a “common burial ground” in 1749, it is an unusually early example of a burying ground established outside the city and as such it reflected the forward thinking of 18th century planners. The cemetery bears witness to the early development of the first major British settlement in Canada and has survived to become an important open space in the city centre. Despite mid-19th century rehabilitation and periods of neglect, it retains its modest scale, rectilinear shape and the haphazard placement of its small dark markers, the principal characteristics of a pre-Victorian burying ground. Preserved in the burying ground are more than 1,300 grave markers. A number of these have outstanding artistic merit. Collectively they preserve a unique record of the cultural cross currents which gave 18th century Halifax its distinct identity.” [7]

The Welsford-Parker Monument

Dedicated on July 17, 1860, this public monument remembers Major Augustus Welsford of the 97th Regiment, and Captain William Parker of the 77th Regiment. These Nova Scotians fought for the British during the Crimean War, and they died on September 8, 1855 at the storming of the Redan fortification at Sebastopol. Also known as the Sebastopol monument, it is not only a rare pre-Confederation war memorial, but also the province’s only large monument.

The larger than life twelve ton lion stands atop the Roman triumphal arch created from Albert County, New Brunswick.

The arch and lion were carved by George Laing, and were funded by public subscription and a provincial grant. Laing was a Scottish carver and Halifax contractor who also erected the County Court House next to the Old Burying Ground, Keith Hall, and the Halifax Club. [8]

Footnotes

[1] Thomas H. Raddall, Halifax, Warden of the North, Toronto, McClelland and Stewart Limited 1948, page 36

[2] Jacqueline Adell, Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada Agenda Paper: The Old Burying Ground, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Architectural History Branch, 1991-05

[3] R. V. Harris, The Church of Saint Paul in Halifax, Nova Scotia : 1749 – 1949, Toronto, The Ryerson Press, 1949, page 217

[4] Adell, Agenda Paper: The Old Burying Ground, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Deed – 29th October 1801 – From the Rector, Churchwardens and Vestry of St. Paul’s to St. Matthew’s Church, respecting the Burying Ground – MSS Old Burying Ground Foundation, Halifax

[5] Adell, Agenda Paper: The Old Burying Ground, Halifax, Nova Scotia

[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] Old Burying Ground Foundation, The Restoration of the Old Burying Ground and the Welsford Parker Monument Fundraising Appeal 1988